Landscape and Architecture - Meanings

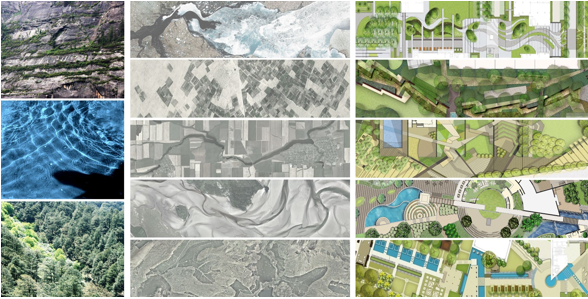

LANDSCAPE is life itself! It is nature. Landscape is 'designed' and also 'exists' all around us. The landscape lies in landscape, creating a continuum. When invoked, it has the ability to 'structure' and 'connect'. As such, in nature too it exists as a set of interconnected networks, perceived as regional patterns. Since it is composed of the living and the non-living aspects of the environment, it itself is always in cyclic motion, exhibiting seasonal and life-cycle changes, and thus involves a deep understanding of processes inherent in nature.

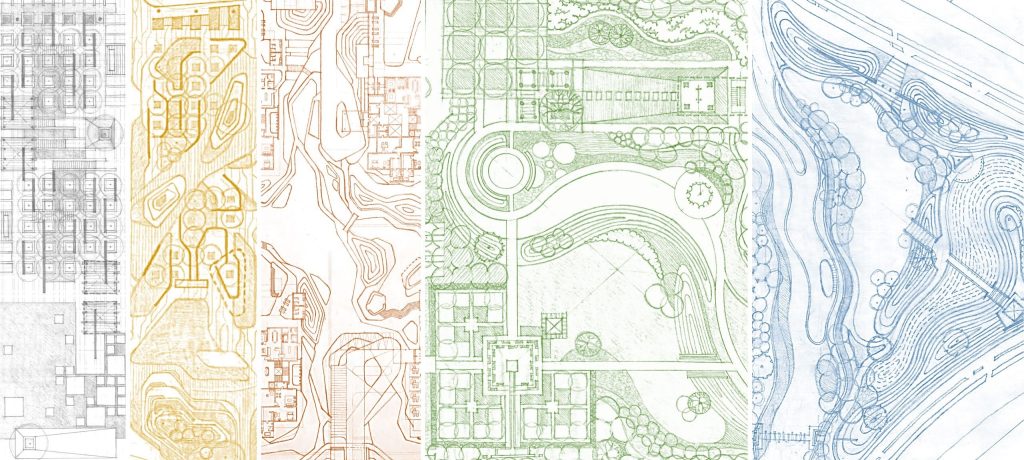

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE begins with the perception and appreciation of interconnectedness of life and nature. It is through this premise that landscape architects are able to objectively discern situations and respond by using their abilities to organize space. The discipline involves multiple skills that span across planning, design, conservation, and management. Landscape professionals deal with scales as small as gardens, going further complexes and regions; touching upon the realm of created landscape as well as pure nature.

In interdisciplinary engagements, landscape architects are the most equipped to offer visionary insights into imagining built form and open space organisations in tandem with natural and urban ecologies to offer creative, responsive and responsible habitats.

While landscape design outcomes may possess the potential of being iconic, experiential and often one of the most decisive factors in determining the sensory, more so the visual, experience; these also constitutes at their core the most 'humble' and 'down-to-earth' act of looking at what is closest to the foot, as one walk through it, what is approachable to the hands as one move through it, and what is visible to the eye at its closest as one experience it. It is also something that is walked over and trampled. It is closest to daily life.

Objectives of Landscape Architecture endeavors

The discipline is vast and deals with varied scale and scope. Study and intervention in landscape encompasses multiple fields of interest, covering life-sciences, earth-sciences, art, history, theory, engineering and technology. As such, landscape professionals may get involved with regional planning, landscape urbanism, design, conservation and management. A general set of objectives and expectations from landscape architecture exercises include the following:

- Formulating thematic narratives that hold complexes and urban precincts together with a rooted philosophy.

- Siting and organising built and open-space components in response to peculiarities of the site, its context and functional relationships engrained in project briefs to create a wholesome experiential realm.

- Expressing crisp attitudes towards relationship with the surroundings, sometimes creating continuums of character and borrowed views and at others, shutting off boundaries to create introverted havens.

- Imparting legible spatial organisations, geometries and order conceived through movement networks, open spaces and buildings to arrive at structured frameworks in response to function and experience.

- Achieving fair segregation of vehicular traffic and pedestrian movement to provide safe, carefree and inclusive environments for its users, considering user groups with varied purpose and physical abilities.

- Adopting a clear approach to nature - land, water and vegetation - the components of landscape, using each fully to create ecologically sensitive, functionally appropriate and experientially rich developments.

- Employing intangible design sensibilities to enrich landscapes with metaphorical meanings, identity and values in relationship to the function, users and society at large.

- Sensitively contributing to environmental issues through considerate planning and utilisation of resources while addressing emerging issues of climate change, sustainability, biophilia and resilience.

- Identifying the predominant function in order to impart a fair value system and relative prominence and accent to experiential, utilitarian and environmental aspects in design.

Issues and Narratives

The role of landscape architects is evolving rapidly with time. Following are key narratives that landscape planning, architecture and conservation dwells upon in situations encompassing different land-uses, project-types, and contexts:

Residential Landscape

The external domain is an arena where lives are lived. It is a place where we give expression to the mutual relationship between life and its environment, coming out into the semi-private realm. Home must be a reflection of our personality. It is imperative that residential landscape is looked at as an aspirational idea of lifestyle, not only reflecting who we are, but also where we see ourselves or who we want to be. Residential landscape likewise, needs to be unpretentious and reflective of our rootedness in culture and tradition. It must represent our values of co-living with nature and engaging with its myriad hues through our inherent system of values.

Today landscape architecture plays a decisive role in group housing and condominiums, influencing choices towards site-planning and themes that evoke sentiments of lives lived fully, over a vast canvas.

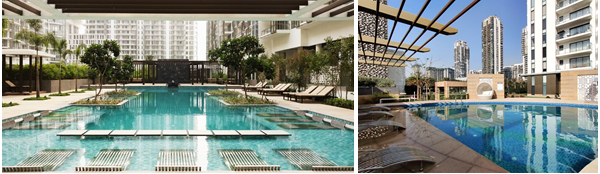

Residential landscape seeks to promote wellness and wellbeing promoting physical and mental health. An array of amenities centered around various age-groups provide an enriching experience, promote companionship and community living. Active recreation is obviously an inseparable constituent of landscape space, be it sports, adventure play-grounds or conventional play zones. Swimming pools too are taking centerstage, not only as functional activity areas, but using larger expanses of water as a quintessential resource to create a unique sense of place. More than active recreation, it is the passive and subtle nature of spatial use that makes residential landscape special. New age communities look towards micro-forests, groves and orchards, productive greens and community farming, meditation zones, areas for festive celebration, flea markets and much more to satiate the zest for a meaningful life.

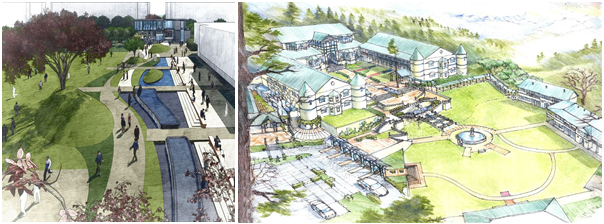

Landscape for Hospitality

Hospitality is an attitude, a virtue. It is an act of cherishing lives. Landscape for resorts and hotels offer unique opportunities to set the stage for an outdoor environment which rather than being a hollow statement of luxury, creates a value proposition from its context. Resort landscape possesses the potential of discerning the unique spatial and visual quality of the place where it nestles, borrow from its scenic or culturally rich setting and frame what it perceives of value. Success of resort landscape would lie in glorifying the setting rather than proclaiming its own presence; thereby forming a continuum between the designed landscape and its natural setting.

Sensitive site-planning is the key to a purposeful resort. Sites often present microcosms of their settings. There are multiple vantage points in a dynamic landscape. It would be most worthwhile to realize a sequence of movement and activities that would successfully reveal the site in an appropriate manner, opening vistas towards directional views and capitalizing on scenic backdrops. The best spots on a site should rarely be built upon. Integrating these as part of the open space ensures perpetuity of the experience and leaves it accessible to a majority of users.

City-hotels are nests outside one’s home. Whether on a business or a leisure trip, one trusts the hotel to be a hospitable, safe and hygienic abode. Landscape of a hotel is often looked at as a statement of opulence and luxury that offers a well-appointed, neat and ordered setting to its visitors and guests. Therefore, landscape design would largely focus on ease and comfort, access, orientation and a collection of amenities that one would hope to have in daily living.

Institutional and corporate landscape

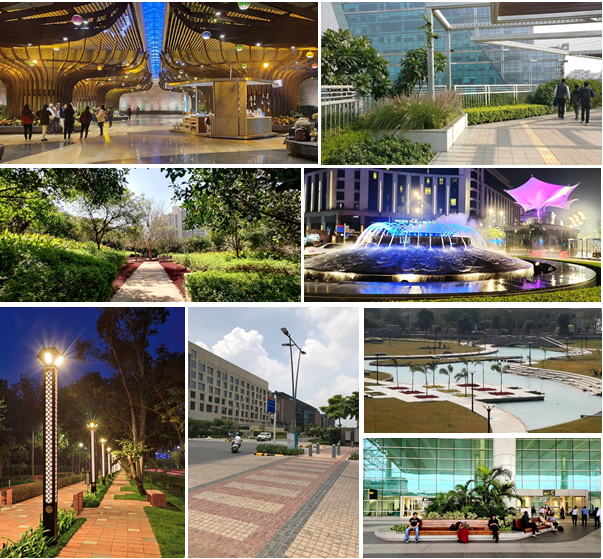

Institutions are places of learning. Corporate houses represent businesses. Nevertheless, both of these are establishments or organizations that stand as fountainheads of the purpose that these represent or philosophies, thoughts and proponents these stand for. Landscape design must be an undertaking that recognises this position and strives to express these values as metaphors, silently conveying the essence, heart or meaning to a discerning observer.

Functionally, institutions must offer spaces that aid in the programs and aims of the institution for the development of their users and communication of their ideas in society. A designer needs to introspect over the fact that each function, as simple as that of moving through, negotiating levels, making space for an interaction or simply laying out gardens, can be done in infinite ways. Which way then would be the closest to aid in disseminating the message of the institution, creating its identity and fulfilling its utilitarian purpose.

One must further realise the immense significance of interstitial or seeding spaces that are actually the essence of an institutional or a corporate landscape. It is in the informal interactions that happen incidentally in these spaces that the nerve-centre of the growth of institutions lies. Design, therefore, needs to give ample attention to the inclusion of such spaces and then do justice to the opportunity these present.

Commercial and retail landscape

The primary requirements for commercial space and retail are easy access, visibility, legible movement, ease of location of entry-points and landmark value. This is what site-planning and landscape design must be mindful of. Multimodal access, looking at pedestrians, self-driven vehicles and those commuting by cabs, poses a challenge of differing experiences of entry. Commuter safety too is a key issue. Security checks need to be thought off well, and integrated with entries.

The site-panning must ensure that its legibility allows for anyone to create a simple mental map for easy way-finding. With retail, it is also crucial to provide equitable visibility and presence along primary movement routes. In addition to this, landscape design needs to be robust in order to take high footfalls. Paving paterns can double up as way-finding tools. Planting must be employed with care not to obscure signage and retail branding. Landscape design needs to accommodate spill-out spaces for restaurants, performance arenas and launch pads for small events and congregation spaces for festive gatherings, flea-markets or corporate events. Place-making is an important objective to impart distinctive character to such complexes. Micro-climate has to be paid atention to, in order for a year-round utility of open spaces.

Industrial Landscape

Functionality, sequence of movement and activities, efficiency and life-safety are the most prominent concern in site planning that the landscape needs to recognize. Industrial estates are corporate in nature and landscape design must strive to capture and express the corporate identity and ethos of the industrial house.

In polluting industries, planting is deployed to create shelter-belts and buffers. Plant material is chosen carefully for bio-remediation, solid waste management, treatment of waste water discharge and soil improvements. Ecological strategies such as bioswales, root-zone treatment, bioretention ponds are possible to create a sustainable green-blue infrastructure, given the relatively larger availability of land.

Objectives of landscape design in areas with visitor and customer interface are governed by aesthetics that befit a style statement commensurate with the stature of the company. Emphasis must be laid on offering a coordinated landscape design that creates an apt visual unit along with buildings.

Cultural Landscape

Landscape character and regionalism derive out of geographical settings and their cultural components. These become crucial determinants of uniqueness and define the 'sense of place'. Patterns on the ground inscribed by the landform, flow of water, growth of natural vegetation, underlying geology, use of land and movement networks give distinctiveness to the setting and are a mute yet strong testimony to myriad natural and human processes.

Noteworthy examples of buildings, complexes, gardens or cities often seem to be nestling perfectly in their geographic settings. This puts forth an important question to ponder: What existed there before this example came up. Hidden in the query is an exploration of geographical settings, and responses to these, over time. It is in the identification of the uniqueness of settings that the successes of responses can be best understood. This, as such, entails a significant step in creating a landscape that can befit regional geography.

Cultural landscape interventions are tailored to serve several key objectives. Understanding patterns in regional landscape to appreciate the connect between natural processes, regional resources and human response is a prerequisite for initiating inquiry into cultural landscape. Tracing temporal continuum helps to discern layers of development and attitudes between culture and nature that has led to the present regional landscape. Documenting cultural landscape units with specific emphasis on significant visual, spatial and ecological value and understanding components and boundaries that constitute these units builds up an inventory that is a critical knowledge base for policy-making and design.

Relationships between historical complexes and their settings help perceive the underlying attitudes and planning principles in their siting and spatial alignment. Detailed research on the spatial organization and underlying philosophical ideas enables recreating landscape around historical buildings in a manner that may be closest to their original intent. Appreciating regional dependency between settlements, heritage zones and movement corridors enables assessment of threats and vulnerability in regional landscape planning.

Apart from paying close heed to activity patterns, congregational needs and other functional aspects, landscape design around places of religious significance or cultural centres in the contemporary context starts from unraveling the layers of historical association, mythological significance, belief systems and events related to the same. Invoking metaphors in design, imparting symbolic meaning and deriving a relevant aesthetic order are the key elements of thought in conceptualizing landscape in the cultural context

Public Realm

Both, urban design and landscape architecture, get extremely limited in their influence when opposed to each other, manifesting as forms and organisations imposed over competing pieces of land, pited against one another. In such a situation, city planning, naturally remains a benign exercise of devising two-dimensional patterns far removed from realities of nature, culture, economics and dynamics. Such exclusivist thinking negates the possibility of a significant contribution of these spatial disciplines to the future of human habitat.

Landscape Architecture, in order to play a significant role in life and experience of the city, has successfully transcended its disciplinary confines, to embrace a set of complex issues around planning, infrastructure, built-form programming and urban design. The landscape urbanism model looks at engaging, radical, creative and more promising forms of practice that are able to transcend the self-imposed professional boundaries and bridge 'scale' and 'scope' with insight and imagination. To take this next leap, such an integrative practice outlines and relies upon the ability of landscape to drive the process of making of a city, not only by organizing complex networks and formulating a 'structure' for urban fabric, but also influencing real estate and its economics in the same stride.

Landscape in the public realm visibly manifests itself as parks, streetscape, plazas or squares, elevated or sub-terranean traverses, special character districts, waterfronts, transport hubs, infrastructure corridors and in several other forms. A detailed analysis of urban situations precedes design intervention. This would begin with establishing the context of the open space in the urban fabric and understanding the role it plays in defining the urban structure or contributing as a shape-giver to the city, its ecological significance in influencing the environmental regime and its temporal usage and activity patterns building connections with lives. It is important to identifying the real and virtual boundaries of the open space that bind it or provide a sense of enclosure to define its physical and visual extents by sieving through the cluter that tends to break up and create fragments. Looking at the history and evolution of the open space in question and the layers of meaning and significance it has acquired over time is crucial too. One needs to discern how built edges and transport networks interact with the open space and how do the two influence each other. Often urban open spaces traverse through different land uses, developing natural variation in their spatial character and usage. People’s association and attachment to the public realm define collective urban memory. These too, need a detailed assessment.

Talking of design, landscape opportunity in urban settings can be looked at as a means of introducing a stylized slice of nature within the city. Public space must be egalitarian and inclusive. Legibility, sense of orientation and landmark value helps in placemaking. Symbolic allusion and thematic relevance enable imageability in public landscape. Unity, integration and gluing of disparate constituents are virtues in landscape, sought after in brownfield developments. Landscapes traverse through and connect components of cities. An instinctive understanding of the city and people helps to engrain the landscape with unique identity and rootedness that users could associate with. Catering to cultural requirements and envisaged activity are obvious outcomes. Design responses also encompass sociological aspects of public open space; reconciling privacy yet openness for public safety. In addition to its spatial qualities, urban landscape has the responsibility to bring in attitudes of sustainability, resilience and robustness to the public realm. Biophilia can go a long way to affirm interconnectedness of human life with its environment.

Inclusivity is the need of the hour

The beginnings of landscape architecture saw the discipline as a 'scientific art' and an 'artful science' that used 'nature' as a medium to create an arena of landscape where lives were lived, expressed and enjoyed. The Western World which identified and named landscape architecture as a discipline also looked with clarity into the difference between a 'garden', 'landscape' and 'nature'. Gardens being examples of modifying nature for aesthetic and spatial content, often relied more on the 'art' of the endeavour and expressed themselves through 'patterns' from that perspective. Nature on the other hand was seen as the storehouse of phenomena, some known and much still less understood. It contained within it the world human existence as well as the universe of life at large. Within this scientific organism called nature, ecological processes operated with unerring precision.

Landscape Architecture borrowed the best of both, invoking art as well as ecology, to create three-dimensional, spatial units that also looked at functional relationships to make cities and regions into seemingly better organised systems to improve the quality of the human world. Conscientious and the responsible minds realised that the field of landscape had more to it than just that, and therefore, the protection of nature and the attitude of invoking ecology in design further enhanced the relevance of the discipline; including life and its environment.

Interestingly, the Eastern World viewed the garden, landscape and nature as a continuum, not physically, but culturally and spiritually, rooted in a way of life that integrated sensory and functional aspects of experiencing and using space. Multiplicity of meaning and interpretation has ever since imparted metaphorical value to landscape, apart from what meets the eye.

Then what has led to this decline in the offerings and quality of landscape architecture. To a large extent, it is the alienation of the terms - 'landscape' and 'architecture' - in the compound which rather should have been welded as a portmanteau. Today, many educational programs in landscape architecture are heavily rooted into scientific and phenomenological research. This is important. However, not at the cost of identifying and honing the capability that is unique to a supposed landscape architect - that of being able to dwell in spatial and temporal reality and organise, plan and design! The industry suffers presently through this limitation.

The grim realities of climate change must bring out fresh attitudes in design that invoke ecology and reflect sustainability. The word 'design', however, holds the key. Attitudes and knowledge would be only as good as information waiting to be processed in the absence of a landscape architect's ability to design. Thought leaders and academic influencers in the discipline must realign their energies to prevent confusion between 'Landscape ecology and environmental sciences' and 'Landscape Architecture'. Endeavours in landscape architecture must strive to build the right balance between the core and its atendant principles.

There are several dichotomies in the discipline that have come out of its teaching and practice. To list a few: clear or ambiguous; utilitarian or experiential; real or aspirational; visual or ecological; intuitive or analytical; art or engineering; literal or symbolic. This is an age of inclusivity. We can no longer afford to treat the pairs mentioned here as oxymorons. In order to create wholesome living environments, boundaries and silos must be deconstructed. The word ‘or’ must be replaced by ‘and’. It is in the virtue of duality that meaningful landscape space thrives.